|

From an early age I

have had a

fascination for exploring and this has become a permanent feature in my

DNA as a mountaineer. In more recent years I have become a great

enthusiast of mountain biking trips and ski touring. For me, life is

too short to be able to visit all the places I'd like to know and

experience. After many backcountry ski trips to snow-covered

areas

all over the world my friend Roger and I began to look for something

different and unusual, a new and refreshing challenge. After bandying

around various proposals we finally agreed. At-Bash, a virtually

unknown name, as far as we were concerned, would be our chosen

destination.

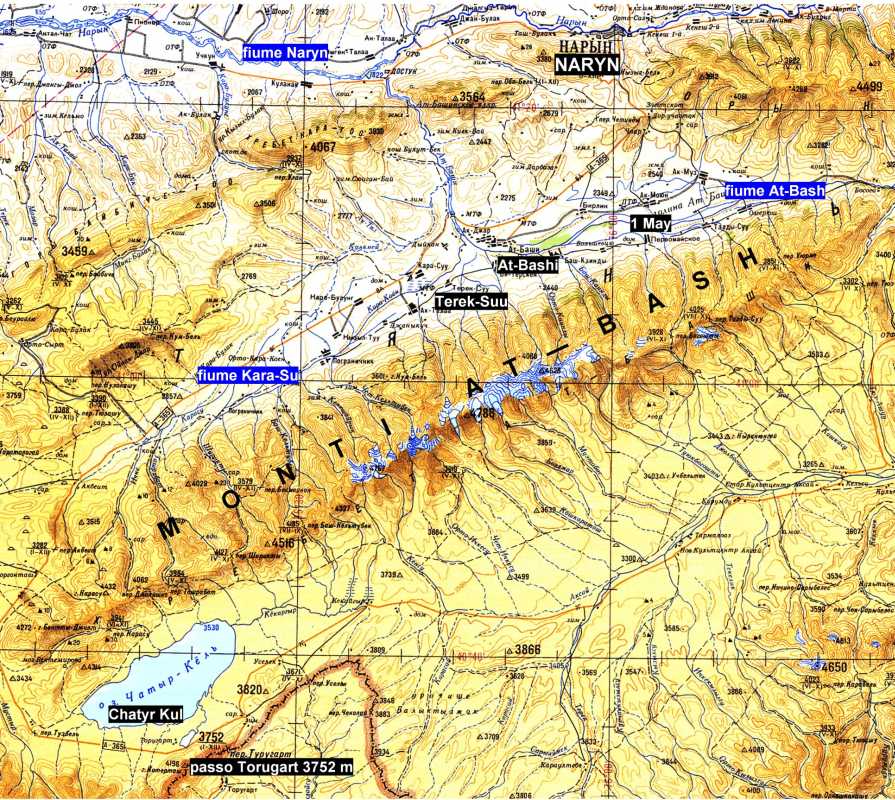

Kyrgyzstan is a mountainous country with a population of over five

million people. The language is written in Cyrillic but rooted in

Turkish like that of the neighboring population of Uighurs in China.

The Kyrgyz Republic was founded in 1990 after the collapse of the

Soviet Union. Like other former USSR states it has had an unsettled

time with authoritarian governments but now, according to our young

companion, Anarbek, a graduate who spent one year studying in the USA

and another in China, has given way to a mature democracy where the

current government can be challenged by the political left or right.

Some

of the mountains of this country, such as the Pic Lenin (7134m) on the

border with Tajikistan, or Khan Tangri (7010m) located where the

borders of Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and China converge, are well known

and have been the focus of former expeditions. Most of the mountain

corrugation, known with the Chinese name of Tien Shan (Celestial

Mountain), is located in Kyrgyz territory. The very distinct range of

At-Bash, isolated by wide longitudinal valleys, which extend in the

ENE-WSW direction for about 100 km. with an average width of 25km and

engraved by very deep transverse valleys and mostly rocky peaks

reaching 4790m, is part of this corrugation. At-Bash, which in Kyrgyz

language means Horse Head, is also the name of the river that borders

the northern slopes and At-Bashi is the name of the largest town in the

valley, located at 2200m above sea level at the confluence of the

At-Bash and Kara-su (Black water) rivers. Here the wide valley provides

a huge inclined plane crossed by the important road linking Kyrgyzstan

with China through the Torugart Pass (3752m). The total population of

the dozen or so villages scattered throughout the valley is

approximately 15,000. The main activities of its inhabitants are

livestock farming (horses, goats, sheep and cattle) and stunted

agriculture due to the short duration of the summer season and the

continental climate where temperatures vary between -40 degrees in

winter and +40 degrees in summer. The river At-Bash is 180 km in

length. It flows through Naryn, the capital city of the region (Oblast).

Information

regarding the At-Bash is scanty. The only topographic maps are old

Russian military tablets with a scale 1:100,000. Digital contour lines

at 25 meter intervals, found on the Internet, are very useful for

installing on a GPS device. From a report available online and updated

in 2015, 'Mountaineering Regions of Kyrgyzstan', written by Vladimir

Komissarov, president of the Alpine Club of Kyrgyzstan (KAC), it

appears that the At-Bash mountains were explored for the first time in

2002 by the same Komissarov together with climbers of the Naryn region,

and then in 2007 and 2011, two British expeditions led respectively by

Pat Littlejohn and Andrew Vielkovsky focused on the valleys of Kensu

and Muzdabas on the southern slopes. Then ... the void. In this

circumscribed region there are more than 60 peaks of over 4000m, more

than 10 higher than 4500m, none of which has ever been climbed. Virgin

peaks. It is no surprise therefore that there were no ski

mountaineering approaches on these southern slopes and even less

surprising that there were no approaches on the north side. How could

we resist the lure of these wonderful mountains.

To feed my desire to revisit Kyrgyzstan there were also great memories

of a trip in the now distant 1998 when we climbed on the walls of the

valleys of Ak-Su[and Kara-Su. Even then our adventurous search for new

spaces in a country that had just gained independence from the USSR was

full of uncertainties and contradictions.

Our

first impression of the capital city Bishkek, which in Soviet times was

called Frunze from the surname of a Bolshevik revolutionary born there,

was very positive. It is very green, very clean, although the traffic,

which is a bit chaotic for a capital city, reflects the current

economic growth associated with Central Asia. Even though At-Bashi is

only 360km from Bishkek we spent 10 hours in the noisy and slow Ural

4320, an old van of military origin - 10 tons, six wheel drive, with a

Diesel 10,000cc engine, which runs 2km per litre at an average speed of

40km/hr on a paved road. We needed this off-road vehicle to access the

valleys. This is part of the charm of these trips in countries where

life is not all neatly planned and organised with rigid timetables and

reliable schedules, where the great virtue of patience leaves large and

unexpected spaces to fantasy and imagination. If we are able to endure

some discomfort, given our western lifestyle which attempts to cater to

our every desire, the satisfaction and wonderful memories reward us

beyond measure.

Leaving

the green valley of Bishkek behind, the landscape becomes more severe:

great open spaces, mountains without names that appear in every

direction, some ups and downs between steep cliffs, wooded slopes

giving way to arid rolling hills as far as the eye can see, with all of

the erosive valleys adding to the beautiful tapestry of colours from

grey to greenish ochre then red. A bright sunset greets us in At-Bashi

where we are accommodated in the house of a matriarchal family (it

seems that everyone obeys the mother). We are given a friendly welcome

and led to large dormitories with walls covered with huge carpets, some

beds and mattresses on the floor. We are given hot food and introduced

to the local environment. The toilets are outside, as in the homes of

our (bis) grandparents, as is the shower that needs to be loaded with

water containers. For personal cleaning we also have access to the

nearby banya, the Russian-style excellent sauna. Although it is very

rustic, it is the place that will regenerate us after each day of

skiing.

The

alarm at six in the morning begins the first day of ski mountaineering

activities. Finally the first sealskins are in place to help us tread

the snows in the At-Bash. The weather is ugly but we start with great

curiosity and enthusiasm as we set out for one of the two main valleys

facing the town which we think, according to our map, are named Acha

Kayindy (west) and Boskurba (east). However we must remember that the

scale of the Cyrillic maps is 1:100,000. As our cumbersome

but

effective Ural limps along bumpy tracks, dirt roads and dry grasslands

we note with a little concern that the lines on the map which we had

hoped would represent access roads are, in fact, only poor

tracks, passable only by horses or perhaps by motorbike. To complicate

matters further, snow is very scarce until you reach high altitudes.

The hands of the clock move round relentlessly and we need to make a

decision if we are

not to waste the day. Yesterday, when we were coming down from the

northern valley, we had noticed that in the easternmost part of the

chain the snow cover was better. We decided to change direction

completely and began to make our way towards the eastern valley until

we reached substantial snow cover. Here we stop Sasha, our driver, whom

we fondly named Gambadilegno (Woodleg) because of his sudden braking of

the vehicle. We attach the skins to our skis and start off in the

direction of a valley with no idea of the destination. Like all the

side valleys of the chain, it creeps southward through the mountains

that exceed 4000m, with the aim of accessing the interior and finding

some interesting elevations for skiing. Our intuition proves to be

correct. After some slightly sloped kilometres, finally steep slopes

surround us. From the GPS we understand that we are in a furrow leading

to a pass that gives access to a 4125m peak listed on the Russian map.

Unfortunately the weather is getting worse, the wind is strengthening

and visibility is poor. As it is getting late and we are alone without

external aid we decide not to venture beyond this point. Bringing a

makeshift stretcher to these endless valleys in the case of emergency

would take a long time. Reluctantly therefore, we do a turnabout.

The

next day, Thursday April 7th, we decide to check the conditions at the

Torugart Pass, which we still hoped to visit. This area which borders

China, is a militarised zone and a special permit which we had already

procured, is necessary for entry. We had only travelled 160km from

At-Bashi but our Ural seemed to suffer altitude sickness more than we

do and it is already afternoon when we reach the place. Despite the

fact that we are now over 3500m there is very little snow. We are

attracted to the southern ridge but, as it happens, the Kyrgyz

government recently sold these slopes to China, from the valley floor

up to the ridges that marked the historical border. They immediately

erected a horrible double barbed-wire fence that prevents any access.

The ridges, now all Chinese, show mountains of over 5,000m, protected

by large ice seracs. On the opposite side there is a huge frozen lake,

the Chatyr-Kul, at 3530m with a surface measuring 180 square

kilometres, just visible because the road is 5 kilometres away. For me

the place has great appeal but I wonder if my friends can appreciate it

as I do. They seem more concerned about not finding snow in the coming

days. Some doubts begin to surface. However, after studying the maps

and digital contour lines that evening we agree that the valley

immediately west of the one we failed to access previously, may lead to

some beautiful snow-covered mountains. We know in which direction we

will point the Ural the following morning without wasting time.

As

Friday 8th April dawns our adventure begins again with another long

valley to access followed by steep, rocky slopes that seem to bar the

way. Proceeding, a little by 'following our nose' and a

little by

GPS, we reach the

top of a steep slope. Finally an outlet appears at a pass at around

4000m. From here we can easily climb to a perfectly skiable peak quoted

on our Russian map as reaching 4,159.2m. Our morale soars as doubts

begin to fade. My mind flashes back to the summer of 1992 when with the

ever present Sonja and three bold young friends we ventured into a

Himalayan valley, without the aid of cartography, searching for some

unknown granite towers to climb. After four days of walking we turned

the corner of an unnamed glacier. There, resplendent before us, stood

the most magnificent granite spiers ever seen by human eyes. It was the

Miyar Valley. Although bad weather forced us to spend four days on a

small ledge a few pitches from the top, denying us the satisfaction of

reaching the summit, those visions, those feelings, the thrill of

discovering a valley, a whole group of mountains hitherto unknown but

which after our discovery became very famous for their climbing

quality, form a more intense and profound memory than many other

experiences. As

Friday 8th April dawns our adventure begins again with another long

valley to access followed by steep, rocky slopes that seem to bar the

way. Proceeding, a little by 'following our nose' and a

little by

GPS, we reach the

top of a steep slope. Finally an outlet appears at a pass at around

4000m. From here we can easily climb to a perfectly skiable peak quoted

on our Russian map as reaching 4,159.2m. Our morale soars as doubts

begin to fade. My mind flashes back to the summer of 1992 when with the

ever present Sonja and three bold young friends we ventured into a

Himalayan valley, without the aid of cartography, searching for some

unknown granite towers to climb. After four days of walking we turned

the corner of an unnamed glacier. There, resplendent before us, stood

the most magnificent granite spiers ever seen by human eyes. It was the

Miyar Valley. Although bad weather forced us to spend four days on a

small ledge a few pitches from the top, denying us the satisfaction of

reaching the summit, those visions, those feelings, the thrill of

discovering a valley, a whole group of mountains hitherto unknown but

which after our discovery became very famous for their climbing

quality, form a more intense and profound memory than many other

experiences.

But

back to the new 'discovery', the At-Bash. The skiing from the peak

quoted as 4159.2m is on perfect firn snow with good slopes up to the

halfway point, then more gentle slopes and the long valley, with a

final surprise on the last meadows where the afternoon melting plunges

us up to our waist, and unexpectedly complicates the last

stretch. Despite the challenges we reach the Ural with smiles on our

faces, feeling super-motivated. The evening is celebrated, first with

beer, which in fact we always have on our table, and then the great

Kyrgyz cognac. Having reason to believe the mountain has never been

climbed before (Komissarov later confirms this), we begin to fantasise

about how to give it a name. Trying to match our Latin imaginations

with local place names we come up with Choku Chichi-bel

(cyrillic ЧОKУ

ЧИЧИБЭЛ, Choku="peak").

Saturday

April 9th. The weather worsens and, while part of the group rests their

weary limbs, fatigued by the Choku Chichi-bel, the fiercest among us

decide to try to force an entry into the Acha Kayindy, the narrow

valley that cast us off on the first day. We have no ambition to climb

any 4000m peaks but we begin to ascend the first mountain with a bit of

snow, just to take a look around. From the point reached the first time

only a few days earlier, Woodleg pushes his terrible Ural along a bumpy

track through meadows and ridges up to the valley and then a little

further... maybe a little too far ... as the ten tons of screaming iron

begin to slip sideways on a narrow bend, coming to a merciful stop at

the edge of a cliff. Feeling like powerless spectators, we breathe a

sigh of relief. Fortunately we manage somehow to turn the vehicle and

get back on track. Finally we are able to start our walk. We shoulder

our skis for a long time because the path is low in the valley. At

first the snow is spread among cypress shrubs (local analogue of our

impassable dwarf pines) and we start to climb zigzag using techniques

dear to us on home terrain when snow is scarce. In the midst of a

snowfall we reach the first summit (3671m) of an endless ridge with a

series of peaks, some exceeding 4000m. However, given that access to

this valley is evidently more complex and lengthy than others and that

our time is limited, with only a few days left of our trip, we decide

to give up on the area. Our experiences so far have given us a better

understanding of the typical topography of these valleys and so, with

the help of the digital contour lines at 25m, more useful than the

Russian maps, we draw on the GPS a hypothetical line that could lead us

to a 4000m mountain the next day. Saturday

April 9th. The weather worsens and, while part of the group rests their

weary limbs, fatigued by the Choku Chichi-bel, the fiercest among us

decide to try to force an entry into the Acha Kayindy, the narrow

valley that cast us off on the first day. We have no ambition to climb

any 4000m peaks but we begin to ascend the first mountain with a bit of

snow, just to take a look around. From the point reached the first time

only a few days earlier, Woodleg pushes his terrible Ural along a bumpy

track through meadows and ridges up to the valley and then a little

further... maybe a little too far ... as the ten tons of screaming iron

begin to slip sideways on a narrow bend, coming to a merciful stop at

the edge of a cliff. Feeling like powerless spectators, we breathe a

sigh of relief. Fortunately we manage somehow to turn the vehicle and

get back on track. Finally we are able to start our walk. We shoulder

our skis for a long time because the path is low in the valley. At

first the snow is spread among cypress shrubs (local analogue of our

impassable dwarf pines) and we start to climb zigzag using techniques

dear to us on home terrain when snow is scarce. In the midst of a

snowfall we reach the first summit (3671m) of an endless ridge with a

series of peaks, some exceeding 4000m. However, given that access to

this valley is evidently more complex and lengthy than others and that

our time is limited, with only a few days left of our trip, we decide

to give up on the area. Our experiences so far have given us a better

understanding of the typical topography of these valleys and so, with

the help of the digital contour lines at 25m, more useful than the

Russian maps, we draw on the GPS a hypothetical line that could lead us

to a 4000m mountain the next day.

Sunday

April 10th. We head with Sasha-Woodleg from the village called 'May

1st' to the Tuyuk Bogoshti, a beautiful, wide valley that runs through

the whole group. This time we stop him before the mud gives us any

problems. We head off, still shouldering our skis, but not for long. As

we walk the first section on skins we are surprised to be joined by a

young shepherd on horseback who is definitely intrigued by our

equipment and intentions.  As

a 'folk figure' he immediately becomes the subject of our photos but

we, in turn, must have looked equally unusual to him, as he now

produces his mobile phone to catch pictures of us. We will no doubt end

up on some Kyrgyz social network as the 'strange visitors' of the day.

The main valley continues rising gently for a long way when suddenly

our 'theoretical' GPS track advises us to follow a rugged and narrow

valley/channel that branches off to the right and culminates in

perfectly snowy peaks with steep access. Our diligent shepherd however

encourages us to continue along the main groove and most members of the

group are inclined to take his advice. But the valley on the right

would allow us to gain altitude much faster. There is a bit of wavering

and indecision. In these moments democracy does not work and an

'executive' decision is required. Earning a moment of unpopularity I

head to the right on ground that is immediately narrow with a lot of

snow and impossible for the young horse to manage. While the horse

gives us an offended look as it turns around, the group follows me with

no objections. We pass easily the initial ravine thanks to the

accumulated snow from avalanches. The valley continues between very

steep side slopes, a mousetrap in wintertime, but now perfectly safe.

It continues toboggan style for several hundred meters to the base of

'our' mountain. The track prepared on the GPS is perfect...

congratulations to Roger, our chief cartographer. We climb a ridge on

the right culminating in a 3954m crest, not a true summit but a kind of

hill. The rest of the group is happy and satisfied with the day's

achievements. Between us and the true summit there is a ridge, mostly

rocky and apparently not simple. I explore a little and find that down

on the right there is a ride so I remove my skis and continue walking. As

a 'folk figure' he immediately becomes the subject of our photos but

we, in turn, must have looked equally unusual to him, as he now

produces his mobile phone to catch pictures of us. We will no doubt end

up on some Kyrgyz social network as the 'strange visitors' of the day.

The main valley continues rising gently for a long way when suddenly

our 'theoretical' GPS track advises us to follow a rugged and narrow

valley/channel that branches off to the right and culminates in

perfectly snowy peaks with steep access. Our diligent shepherd however

encourages us to continue along the main groove and most members of the

group are inclined to take his advice. But the valley on the right

would allow us to gain altitude much faster. There is a bit of wavering

and indecision. In these moments democracy does not work and an

'executive' decision is required. Earning a moment of unpopularity I

head to the right on ground that is immediately narrow with a lot of

snow and impossible for the young horse to manage. While the horse

gives us an offended look as it turns around, the group follows me with

no objections. We pass easily the initial ravine thanks to the

accumulated snow from avalanches. The valley continues between very

steep side slopes, a mousetrap in wintertime, but now perfectly safe.

It continues toboggan style for several hundred meters to the base of

'our' mountain. The track prepared on the GPS is perfect...

congratulations to Roger, our chief cartographer. We climb a ridge on

the right culminating in a 3954m crest, not a true summit but a kind of

hill. The rest of the group is happy and satisfied with the day's

achievements. Between us and the true summit there is a ridge, mostly

rocky and apparently not simple. I explore a little and find that down

on the right there is a ride so I remove my skis and continue walking.  Three

of the group follow me. In a connecting portion between the rocks where

snow has drifted I sink down to my armpits. Fortunately Mirco, who

weighs 10k less than me, is able to pass the next three steps needed to

reach the rocks. From here we have no difficulty reaching the summit

where the altimeter marks 4016m. We hug and raise our arms to greet our

friends who remained on the crest. They cannot resist the temptation to

join us and as they in turn make the journey we share our moment of

stardom. We continue to celebrate our achievement that evening after

our descent on this perfect firn snow with a sauna, yet another toast

and another beautiful evening in good company, with the proposal to

dedicate the new mountain to the young Chiara, hence Choku Kiara (ЧОKУ

KИAРA). Three

of the group follow me. In a connecting portion between the rocks where

snow has drifted I sink down to my armpits. Fortunately Mirco, who

weighs 10k less than me, is able to pass the next three steps needed to

reach the rocks. From here we have no difficulty reaching the summit

where the altimeter marks 4016m. We hug and raise our arms to greet our

friends who remained on the crest. They cannot resist the temptation to

join us and as they in turn make the journey we share our moment of

stardom. We continue to celebrate our achievement that evening after

our descent on this perfect firn snow with a sauna, yet another toast

and another beautiful evening in good company, with the proposal to

dedicate the new mountain to the young Chiara, hence Choku Kiara (ЧОKУ

KИAРA).

Monday

11th. April... our last day. It would be nice to try the 4000m peak we

missed on the first day but with the accumulation of fatigue this might

prove too ambitious. Furthermore, the weather forecasts give a picture

of deteriorating weather conditions. Once on the road we decide to head

for a highly visible peak and try to track a hypothetical itinerary

using GPS. We cannot find the track that should lead us to our chosen

starting point. Eventually Sasha stops the vehicle at the beginning of

the forest where a very narrow valley begins. At least it is snowy. To

avoid shouldering our skis we climb this steep, dense forest. Once

again we are reminded of our home terrain. When we emerge from the wood

we are rewarded by the sight of a couple of valleys and right above us

a beautiful snow-covered peak (3650m), which we reach quite easily and

from which we serpentine down, again with satisfyingly firn snow. The

summit on which we had initially set our sights is on the continuation

of the ridge which is marked on the Russian map at 3806.6m but we are

happy and content with our achievements.

We

are already at the end of a week of exhilarating experiences. Our

sincere thanks go to the family who hosted us and to Sasha

Woodleg,

our driver and Anarbek, our guide. The hospitality we received was

wonderful and the Kyrgyz people will remain in our memories with great

affection. After Patagonia '84, Karakorum '88, the Indian Himalayas '91

and '92 and Greenland '96 I thought my opportunities for discovery

could not be surpassed. But, as the world becomes increasingly

globalised, to discover and climb virgin mountains, explore unknown and

unmapped valleys and even baptise unnamed peaks is still possible. As a

rule I would not use the word 'exploratory' to describe our trips as I

feel it is often used out of turn by those travelling for the first

time in a place that has already been described and mapped. However,

our experiences here at At-Bash can only be described as a true 'ski

mountaineering exploration'. Who knows how many places like this still

exist hidden in the folds of the planet? Hopefully, the serendipity

which led us to the At-Bash will lead us to more discoveries in the

future, maybe even just by pointing the chance finger at the world

map! We

are already at the end of a week of exhilarating experiences. Our

sincere thanks go to the family who hosted us and to Sasha

Woodleg,

our driver and Anarbek, our guide. The hospitality we received was

wonderful and the Kyrgyz people will remain in our memories with great

affection. After Patagonia '84, Karakorum '88, the Indian Himalayas '91

and '92 and Greenland '96 I thought my opportunities for discovery

could not be surpassed. But, as the world becomes increasingly

globalised, to discover and climb virgin mountains, explore unknown and

unmapped valleys and even baptise unnamed peaks is still possible. As a

rule I would not use the word 'exploratory' to describe our trips as I

feel it is often used out of turn by those travelling for the first

time in a place that has already been described and mapped. However,

our experiences here at At-Bash can only be described as a true 'ski

mountaineering exploration'. Who knows how many places like this still

exist hidden in the folds of the planet? Hopefully, the serendipity

which led us to the At-Bash will lead us to more discoveries in the

future, maybe even just by pointing the chance finger at the world

map!

Paolo

Vitali, April 2016

Photos and maps by Ruggero Vaia and Paolo Vitali

Expedition

sponsored by CAI-SAT section of Cavalese

Skiers

of the group

Sonia Brambati, Franz Carrara, Gianni Corti, Mirco Gusmeroli, Denis

Ganz, Vigilio Ganz, Giulia Meregalli, Renato Pizzagalli, Fedorino

Salvadori, Franco Scotti, Ruggero Vaia, Paolo Vitali.

Ski tours

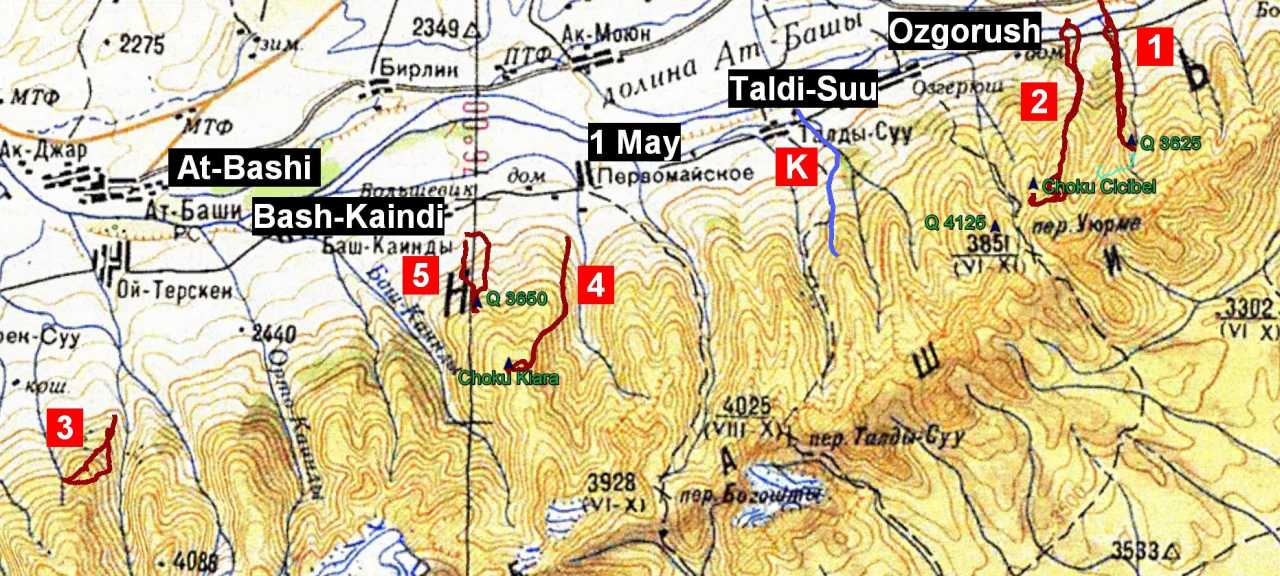

1) April 6 2016 – Q. 4125 m, valley Karaili Bulak

(tentative, till quote 3674 m)

2) April 8 2016 – Q. 4159,2 m, valley Sari Tal – proposed

name Choku Chichi-Bel (ЧОKУ ЧИЧИБЭЛ)

3) April 9 2016 – Q. 3671 m, valley Acha Kayindy

4) April 10 2016 – Q. 4016 m, valley Tuyuk Bogoshti – proposed name

Choku Kiara (ЧОKУ KИAРA)

5) Aprile 11 2016 – Q. 3650 m (lower-summit of Q. 3806.6 m), valley

Kichino Kek Djol

Practical info

Periodo:

in winter, temperatures can reach -40 C (-40 F). However in April the

sun heats up very quickly and the snow at low altitude disappears

quickly. So, at the beginning of April you must consider the need for

shouldering skis at times. The end of March might be a better time

provided there have not been recent heavy snow falls, in which case you

must be very careful on the steep slopes. In the middle of winter it is

probably possible to ski with beautiful powdery snow but make do with

the outer peaks of the chain without going into the valleys. Periodo:

in winter, temperatures can reach -40 C (-40 F). However in April the

sun heats up very quickly and the snow at low altitude disappears

quickly. So, at the beginning of April you must consider the need for

shouldering skis at times. The end of March might be a better time

provided there have not been recent heavy snow falls, in which case you

must be very careful on the steep slopes. In the middle of winter it is

probably possible to ski with beautiful powdery snow but make do with

the outer peaks of the chain without going into the valleys.

Access:

By

air to the capital Bishkek. Currently the most frequent flights are

those of Turkish Airlines and Aeroflot. A good paved road covers the

distance of about 360km between Bishkek and At-Bashi. In At-Bash an

off-road vehicle is necessary to access the valleys.

Accomodation:

In At-Bashi the family of Mrs. Eva Aka Turunkan offers half-board

accommodation, ul.Arpa 25, tel. (+996) (0) 3534 23944, mobile (+996)

(0)773 105774.

Exchange

rate: in April 2016, the exchange rate was approximately

78 “Kyrgystani Som” for 1 €.

GPS:

very useful for orientation in the valleys and in case of bad weather.

The map of Kyrgyzstan is available on Openmtbmap.org and for a moderate

price, also the useful contour lines.

Maps:

the image-file of the Russian army maps are available on loadmap.net;

the best available scale is 1: 100,000 (1: 100k).

Telephone:

the best solution is to buy a local prepaid card, the cost of

international calls are much cheaper than any offer of European

operators, whose basic rates arrive at 6 € per minute. In the valleys

of course there is no signal, but there is in the towns and along all

roads.

Self

rescue:

Carefully consider the fact of being completely alone in the valleys;

in these places you cannot expect rapid external aid, so it is

necessary to have self-rescue equipment and provide for the possibility

of setting up an emergency stretcher.

|